By Koryn S. Hare, M.A. Steele, and K. M. Wood

Department of Animal Biosciences,

University of Guelph

Calving season is a demanding 24-7 job:

we check our cows frequently, making sure that they are not taking too long to calve and intervening when needed. Next, once the calf is on the ground, we ensure that mom is mothering up and that the newborn does not get chilled and is on their feet as soon as possible. Finally, we make sure that they get the colostrum they so critically need at that age to establish their immune system. But how often do we think about the quality of colostrum our cows are producing? Are there steps we can take before calving to make sure mom produces the best colostrum she can for her calf?

How can late gestation nutrition help? At the University of Guelph and University of Saskatchewan, we have been working to understand what nutritional factors influence beef cow colostrum quality. We first started looking at the protein content of a beef cow’s diet during her third trimester. With adding more protein, 8 weeks before calving, we expected that the cow would produce more antibodies and therefore have greater antibody levels in her colostrum. We took colostrum samples at calving and analyzed the fat, protein, lactose, and antibody content. While extra dietary protein (~30% more than requirements) did not change the amount of antibodies in colostrum, we found it reduced the concentration of fat in her colostrum by half (7.0 to 3.4% colostrum fat, normal-protein compared to high-protein diet). What likely happened, is that feeding more protein reduced how much body fat the cow was mobilizing before calving, leaving less to be incorporated into her colostrum. While this is a good strategy for the cow to maintain condition, it might not be beneficial for the calf since newborns need energy-dense colostrum to support their metabolism; particularly, during the cold, wintery months during which they are born. In a follow-up study, we found that additional protein (both at 100% or 110% of requirements) at the same energy of the previous trial supported maintaining cow body weight, but in this study colostrum composition or passive transfer of antibodies to calves was not impacted.

After looking at dietary protein, we started looking at dietary energy with a special interest in energy sources that would increase the cow’s blood glucose before calving. In Current studies at the Ontario Beef Research Center (University of Guelph), we fed cows and heifers three diets 8 weeks before calving that were designed to provide low, normal, and high amounts of energy. We used high-moisture corn grain and whole corn in the normal and high energy diets to increase the dietary energy density. We undertook milking a third of the cows after they calved using a portable milking machine, weighed the colostrum and sent samples for analysis (shown in Figure 1).

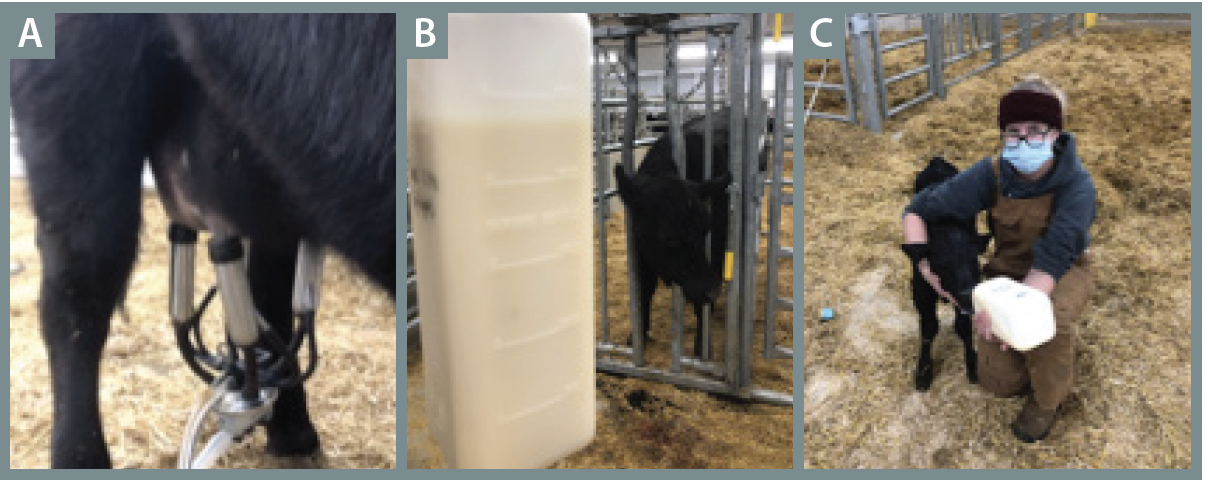

Figure 1.

A. Milking teat claw attached to the udder of an Angus-Simmental crossbred beef cow at the Ontario Beef Research Center.

B. Full colostrum yield from a primiparous Angus-Simmental crossbred beef cow.

C. Bottle-feeding colostrum back to an Angus calf after sampling colostrum.

More importantly, we showed with energy supplementation, it is possible to affect antibody concentration in beef cow colostrum. We found that the antibody concentration in colostrum decreased when we provided the cows with more energy before calving. However, similar to the nutrient components, this is a dilution effect because the cows that ate higher energy diets also produced more total colostrum, therefore producing more total antibodies in their colostrum then the others.

So, what can we take away from these studies? Nutrition in late gestation is an important factor that affects the quality of colostrum that beef cows produce. Dietary energy appears to have more impact on colostrum than dietary protein when supplemented 8 weeks before calving and can increase the total amount of nutrients and antibodies that are available to beef calves at their first meal. That said, we cannot discount the importance of adequate dietary protein because cows need to have enough protein in their diet to support body condition and make use of the extra energy they are provided before calving. These changes in colostrum quality can also potentially have longer lasting impacts on calf health, growth, and performance. Continuing research in our lab groups is trying to better understand these lasting impacts and what the best strategy to “super-charge” colostrum.

This article was written for the Fall 2022 Beef Grist. To read the whole Beef Grist, click the button below.